The letter from my father five years after he died

My father never wrote me real letters. My mother was the letter writer in the family. Blue aerogrammes filled with choice tidbits of family gossip, menus from weddings I had missed, long-distance advice on how avoid colds and sore throats. She sometimes wrote sideways or upside down or along the margins to make sure not an inch of space was wasted. If I tore the letter open incautiously, I risked never getting to know what they had eaten at Cousin Ramita’s wedding. Mail could take three weeks to wind its way from Calcutta to California and the gossip was usually long stale by the time the letters reached me. But I devoured them nonetheless.

My father, on the other hand, just scribbled notes in the tiny spaces she left him. Notes written, I suspect, under duress. “Write to your son,” she must have told him. So he did.

How are you? Happy birthday. We are well. Take care of yourself.

Thus the first real letter I got from my father came as a surprise. Not just because he was such an unlikely letter-writer but because it reached me five years after he had died.

My niece had been rummaging through his old desk and found a notepad in there gathering dust. My father had many such pads, filled with meticulous details of his investments. But this one had something else – letters addressed to my mother and me, written in his angular, almost cuneiform handwriting, preparing us for a life without him. Letters that were not dated, letters never meant to be posted. He didn’t even have the chance to tell us where to find them.

There were no shocking family secrets in them. No great confessions. “I am nobody so important that when I am gone, I will be really missed by anyone other than you,” he wrote. “Don’t worry about doing elaborate funeral ceremonies for me. Don’t shave your head. Don’t follow all those rules and rituals.”

We did not get the letter in time. We followed all the rituals and rites. I shaved my head like a dutiful Hindu son, sat cross-legged on the floor, clutching flowers by the fistful, surrounded by incense smoke and repeated what the priest told me to say.

My father died while I was still in California. By the time I managed to fly back to India he had already been cremated. He had been a quiet man, dignified but unassuming. He had no passion for pipes or Scotch or designer shirts. He wore whatever clothes my mother laid out without fuss. I never knew what to get him for his birthday. So I just got him aftershave after aftershave, year after year.

Adulthood had made us polite strangers, immigration even more so. We did not know what to say to each other. He wanted to tell us about the investments he was making for us. “Just tell me where to sign,” I would say impatiently. We would tease him that all he wanted to talk to us about was signing forms.

But perhaps he said nothing because we never asked him anything. About his years in London working for British Rail and how he made that long journey from India by ship. About building bridges in tiger-infested jungles in Central India. About what he thought of the world around him. Perhaps that was why he finally sat down at his desk, in his study, uncapped his pen and started writing letters to us.

“I have very little sense of God,” he wrote. “I just think what was meant to happen happens. Perhaps it was just time for man to go to the moon. Or it was time for the atom to be split. Perhaps it is all part of a timetable somewhere. I do not know why. Or whether it is for good or for bad.”

When I left for America for the first time, like a dutiful father he organised the air tickets, the precious foreign exchange, the bank statements I needed for my visa interview. But while aunts warned me against wayward American girls and my mother tried to give me a crash course in how to cook, my father offered no advice, no admonitions, no pep talk. He always said he had raised us to make our own choices. But in the letter he tells me not to do work that only feeds my self-interest. “If it can help others it will fill your heart as well. But if you help others, be careful. Don’t be tempted to think of yourself as superior to them.” Be wary of the desire to inflate your ego, he warns, to prove you are right and others are wrong. “Don’t belittle yourself. There is no frustration greater than that.”

Reading the letters I could hear my father talking in a way he never did while he was alive. And for the first time I also felt the finality of his absence. I had not been there when he died. I had not seen the hospital rooms. I did not know the name of the night nurse or the day nurse. I had not fluffed a pillow. I had not lit the funeral pyre. Emigration to the United States insulated me from it all and in the process had rendered the death of a parent, one of the final rites of initiation into adulthood, strangely unreal. It was something I heard about but did not get to see. By the time I walked into our house he was a photograph on a cabinet.

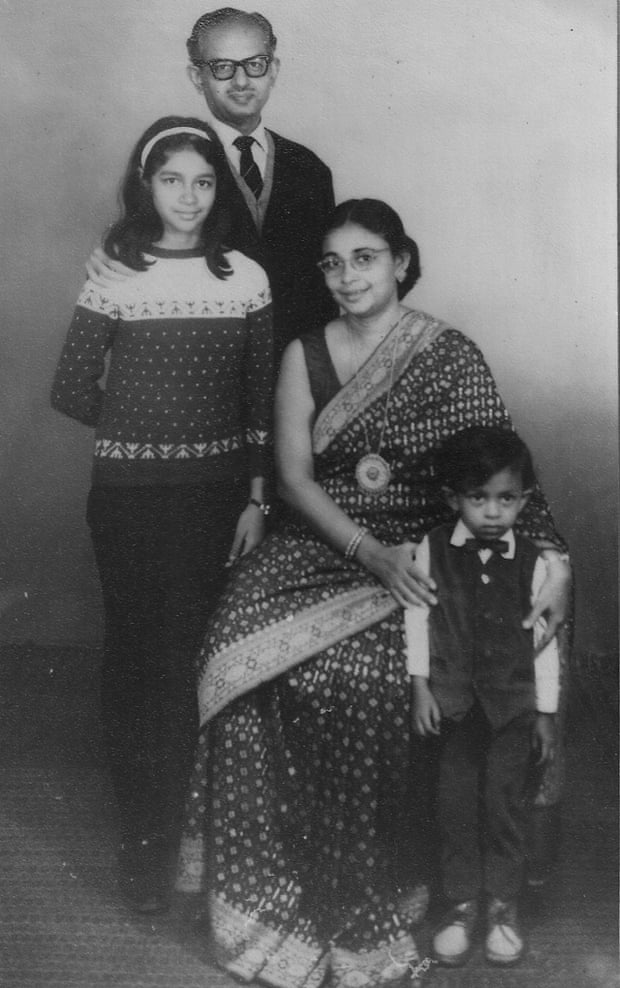

For weeks I would listen to my mother tell and re-tell the story of the morning my father died and memorise each detail, as if in doing so I could surreptitiously sneak into that family tableau. It was the only way I knew to remind myself that he was really gone, not just sitting quietly at his ink-stained desk somewhere, sorting papers into pink and green manila folders. I had little else to hold on to from him, except for those second-hand stories. While we have crumbling albums filled with black-and-white family photographs, there are very few pictures of my father with us. He was the one behind the camera. We have old spool tapes of my sister and me reciting nursery rhymes, babbling but my father is just the voice in the background making encouraging noises to coax us along.

Now, suddenly, years after his death I could suddenly hear my father’s voice talking again. Really talking. Not saying “Sign here” or a hurried “How are you? We are well,” over a crackling phone line before handing it over to my mother. And though his letters are unsigned, not neatly tied up with “Love, Baba” at the end, every time I read them I finally get to hear him say goodbye.

Don’t Let Him Know by Sandip Roy is published by Bloomsbury, £14.99.

Photo by Bishan Samaddar, The Guardian

Originally published by the Guardian, author Sandip Roy.

Leave a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.