How do we protect our digital legacy after death?

UK – In the old days we stored our treasured memories in photo albums and paper diaries. Physical things which could be passed on in a will. But now, in our online lives our memories – our thoughts, feelings and images – are scattered to the four winds of the internet, and stored on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and WhatsApp.

But who actually owns them?

And how do we ensure that the people we want to inherit them, our loved ones, actually do?

Louise Palmer knows only too well how difficult it can be.

Her 19-year-old daughter Becky loved sharing her life on Facebook.

When she fell terminally ill with a brain tumour, and lost speech and movement, Louise would log in with Becky to help her stay in touch with her friends.

Becky died in 2010 but Louise continued to access her account to feel close to her daughter.

“It was really important,” she told me.

“When you’ve lost a child, and losing a child is the worst loss there is.

“You become very, very fearful that other people are going to forget them.

“So to be able to go on there and read not only what people have put on her wall, but private messages that people had sent as well.

“It was reassuring me that she wasn’t going to be forgotten.”

Memorialised account

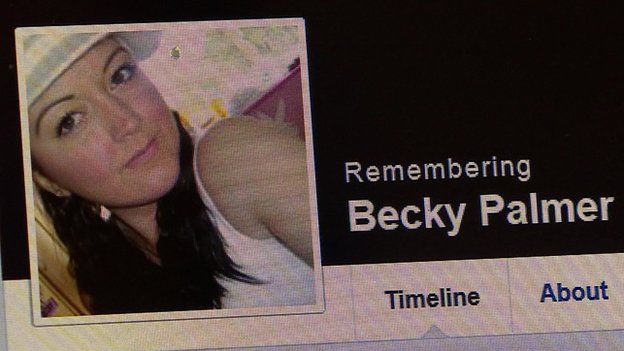

But then Facebook locked or ‘memorialised’ Becky’s account.

Louise wrote to them explaining the tragic circumstances of Becky’s death and expressing her desire to read the private messages on her daughter’s page and to keep it tidy.

Becky’s Facebook account was memorialised

She received this reply: “Hi Louise, We are very sorry to hear about your loss. Per our policy for deceased users, we have memorialized this account.

“This sets the account’s privacy so that only already confirmed friends can see the profile or locate it in Search.

“The Wall will remain, so friends and family can leave posts in remembrance.

“Unfortunately, for privacy reasons, we cannot make changes to the profile or provide login information for the account.

“We apologise for any inconvenience this may cause. Please let me know if you have any further questions. Thanks for contacting Facebook.”

Lack of awareness

Louise then wrote to Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg, but did not receive a reply.

New YouGov research commissioned by the law firm Mishcon de Reya reveals an alarming lack of knowledge of who owns our online material.

Around one in four simply have no idea, while one in three believe it belongs to Facebook after death.

Who do you think owns content?

YouGov asked 2,185 adults: In the event that a Facebook user passes away, who do you think, by default, owns their Facebook content?

36% said Facebook

20% said next-of-kin

17% said no-one

27% said they didn’t know

So who does own our online content?

Mark Keenan, a partner at Mishcon de Reya says: ‘It’s a legal minefield, it’s the new frontier.

“People are just not reading the terms and conditions, and what we are seeing is a real increase in disputes between competing family members and the service providers.”

There are no norms or standard practice among online providers for how digital assets are passed on to heirs.

Clear instructions

Last year the Law Society warned people to leave clear instructions about what should happen to their social media, computer games and other online accounts after their death.

It stressed that having a list of online accounts, such as email, banking, investments and social networking sites will make it easier for family members to piece together a loved one’s digital legacy, and provide the best chance for the wishes of the deceased to be fulfilled.

It is not only sentimental material that can be lost.

Digital assets can also include things with a real monetary value such as music, films, email accounts, computer game characters, domain names, air miles, reward points, PayPal and Bitcoin accounts.

And it is not just small change.

A virtual space station has been sold for $330,000 on a game called Project Entropia – though whether that kind of asset could be passed on would depend on the game’s terms and conditions.

Gary Rycroft, a member of the Law Society Wills and Equity Committee, said people should not assume family members know where to look online and to make details of their digital life absolutely clear.

“If you have a Twitter account, your family may want it deactivated and – if you have left clear instructions – it will be easier for your executors to have it closed.

“If you have an online bank account, your executors will be able to close it down and claim the money on behalf of your estate.

“This is preferable to leaving a list of passwords or PINs as an executor accessing your account with these details could be committing a criminal offence under the Computer Misuse Act 1990.

“It is enough to leave a list of online accounts and ensure this is kept current.”

Passwords remain secret

Not that many of us tell anyone what our passwords are.

The YouGov research found that 52% of us said that no-one, including friends and family, would be able to access our online accounts should anything happen to us.

Becky was very close to her mother

In February Facebook offered customers in the US the option of deleting an account when they die, or appointing a friend or relative to take control of some parts of it.

But that doesn’t apply here.

In a statement they told me: “When a person passes away, their account can become a memorial to their life.

“The Profile no longer appears in public spaces, so that grieving friends and family can continue to view the comments, photos and posts of their loved ones.”

But that wouldn’t include private messages on Becky Palmer’s site, or allow Louise to manage it.

With many cherished memories of her daughter locked up online, Louise Palmer relies increasingly on a few home videos for comfort.

She understands that there are reasons for Facebook’s privacy policy following a death – some people may not want anyone picking over details of their private life online.

But she says that there were no secrets between her and her daughter.

They shared everything in life.

She told me: “I’m her mum and this was her Facebook page, and its contents I felt were my legacy.

“Her online stuff should now be mine to be able to access.”

Digital memories

At their inception social networking sites were largely the province of the computer savvy young.

A deluge of personal material flowed online, and no one was thinking about what might happen to it after death.

Now that social networking and the internet are well past their infancy, it is surely prudent for us all to consider how to pass on our digital, as well as our earthly, legacy.

Originally published by BBC News, author Clive Coleman.

Leave a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.